Surprisingly, one of the most overlooked parts of flash chromatography is the very first step—loading the sample onto the column. At first glance, this might seem simple, but in practice it requires more care than many expect.

Students often learn the theory of separation and elution, but the hands-on details of loading are not always taught. As a result, while you can technically achieve separation by just adding the mixture, you may end up with poor resolution, weak sensitivity, or low selectivity.

Therefore, the real key to successful flash chromatography is knowing how much sample the column can handle and deciding whether to use a wet load or a dry load. These choices directly affect the quality of your separation and the efficiency of your run.

When running chromatography, scale always matters. If you are working with only a few milligrams of material, overloading the column is rarely a problem. Instead, your biggest challenges may be poor detection or even unexplained sample loss. Many chromatographers can confirm that small samples sometimes seem to vanish once they hit a flash column.

On the other end of the spectrum, very large samples—especially complex mixtures—can be just as troublesome. They may prove difficult to separate cleanly at scale. Therefore, the first step in proper method development is to determine the loading capacity of your flash column.

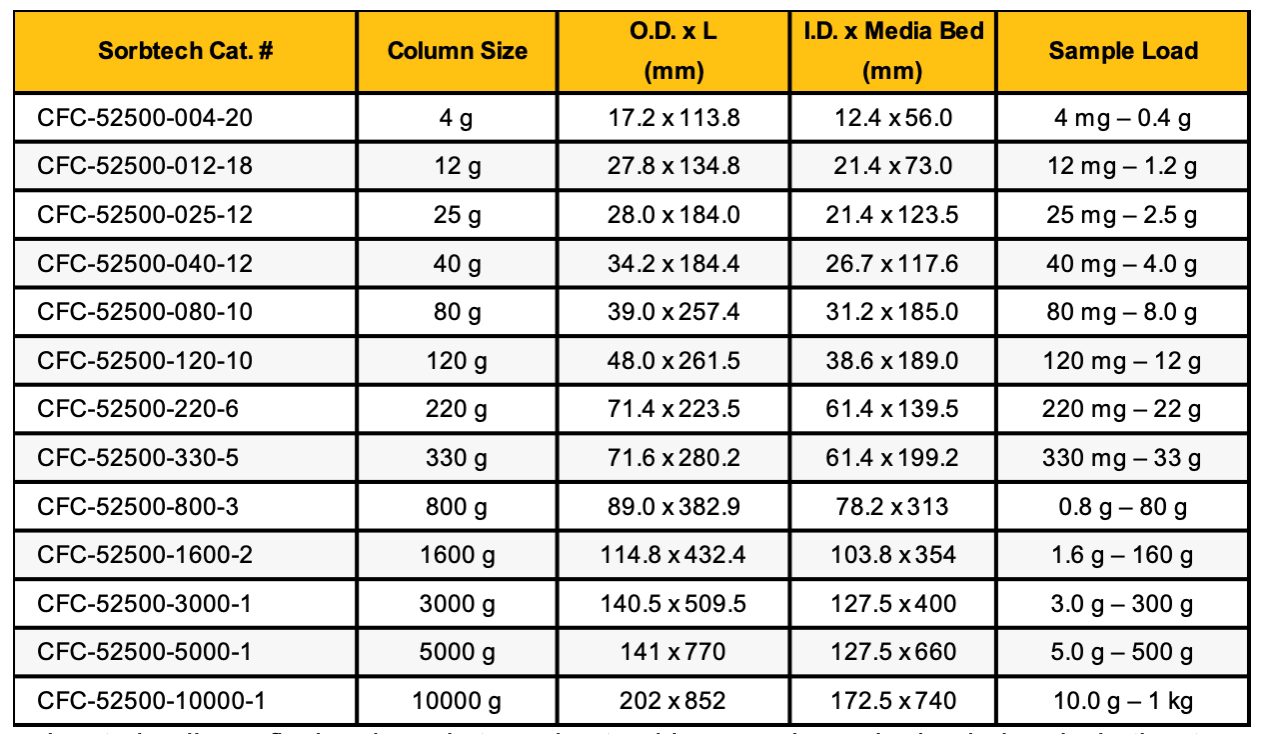

Manufacturers often provide this number, but many factors influence the real limit. For silica-based columns in normal-phase chromatography, the maximum load typically falls around 10% of the media weight. Some sources report up to 20% on spherical media, and while this can sometimes work (for example, with simple mixtures or low impurity levels), using 10% as a rule of thumb is usually safer.

We also recommend following a sample load table as a general guide. Keep in mind that purity requirements, sample homogeneity, and dilution will all affect the actual load you can use.

For reversed-phase hydrocarbon-bound flash columns, capacity is much lower—usually only 1–5% of the media weight. It’s important to remember that these figures are maximums. In most cases, staying under the limit will give you more reliable results.

Finally, don’t forget about minimum loads. Putting 5 mg of material on a 300 g column is almost certain to cause recovery problems. Most manufacturers include a recommended minimum, and that should be treated as your baseline when planning runs.

When planning a flash separation, you need to think about more than just sample weight. Mixture complexity and concentration also matter. For example, there is a big difference between injecting a dilute 100 mg solution and injecting a neat 100 mg liquid. By accounting for dilution early on, you can avoid damaging a column from overload and prevent the frustration of replacing it too soon.

In addition, the separability of your compounds plays a major role in choosing the right column. If your compounds have very different Rf values, you may be able to use a smaller column without issue. However, if the compounds are very similar, you will likely need a larger column with more media to gain the efficiency needed for separation. For instance, if retention times differ by only seconds on an HPLC, scaling up the column media weight is often necessary to achieve preparative results.

That’s why we strongly recommend starting with a quick TLC. This small test will give you essential information about both Rf and CV values, helping you set the right conditions for a successful purification.

When it comes to loading, you have two main options: wet loading and dry loading. The difference comes down to whether the compound is dissolved in the starting mobile phase. Wet loading, often seen as simpler, is the method most chemists prefer. In this case, you dissolve your mixture in a minimal amount of either the isocratic or initial mobile phase (for gradient runs) or in a solvent weaker than your eluant, and then inject it directly onto the column with a syringe.

Sample Load Calculator

Excel Macro

Use this macro to determine the appropriate sample load volume based on column dimensions and sorbent particle size.

You may have to authorize this macro in Microsoft Excel prior to use.

by Dr. Robert Kerr, Director of Research and Development, Sorbent Technologies, Inc.

Wet Loading

To carry out a wet load, you need to follow a few key steps and pay close attention to certain details.

First, make sure your mixture is easily soluble in the chosen mobile phase or solvent. You want to use the smallest amount of solvent possible, since too much can cause premature elution. If your mixture is difficult to dissolve, wet loading may require an excessive amount of solvent, which can hurt the separation.

Second, never use a solvent that is stronger than your mobile phase in terms of elution power. If you do, your separation will not perform as expected and will likely fail.

Finally, be careful during injection. Many chemists inject their dissolved mixture but remove the syringe too quickly. Because backpressure is often generated during injection, you must wait until there is no resistance before removing the syringe. Otherwise, the sample can leak back out of the top of the column.

Dry Loading

At first, dry loading may seem intimidating, but over time the process has become much simpler thanks to better tools. In this method, you adsorb the sample onto a solid support—commonly silica, Celite, or another adsorbent—and then introduce it to the system as a fine powder.

Traditionally, this required removing the top of the column and adding the powder directly to the packing. Today, solid loaders make the process much easier. These specialized tubes hold the adsorbed sample and deliver it into the system without disturbing the main column. The mobile phase flows through the solid loader first, carrying the sample into the column in real time.

Dry loading works best when your sample is not soluble in the starting mobile phase or when you plan to use a gradient that begins elution later. However, you must avoid using too much adsorbent material. Excess silica, Celite, or other solid phase can cause band broadening or delay separation. Instead, add just enough solid support to make a free-flowing powder. A common method is to prepare a slurry with solvent and then evaporate the solvent until the powder is dry.

With all this information, it may feel overwhelming to decide the best way to load a column for a specific synthesis or process. Fortunately, there are practical strategies that make the choice easier. Many chemists rely on known mixtures with well-defined separations to test whether a particular loading process or flash column size is appropriate.

In addition, reproducibility and robustness can be checked by reinjecting these reference mixtures after column runs. Tracking how the column performs over time reveals problems such as bleeding, poor resolution, unexpected shifts in elution, or delayed separations.

Moreover, proper maintenance extends the life of your columns. Good cleaning techniques, regular rinsing, and avoiding overload allow many columns—especially reversed-phase columns—to deliver consistent, reproducible results over multiple uses. On the other hand, preparative silica columns rarely hold up as well. Impurities often get trapped inside, unwanted chemical interactions build up, and eventually, the column loses its separation power.

Ultimately, trial and error remains an important part of the process. Running small pilot tests before committing to large-scale chromatography helps confirm loading principles and ensures that your separation will work effectively at scale.

About the Author – Ransom Jones

Analytical Scientist at Mikart LLC, focusing on product development for drug substances and drug products. MSc in Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Sciences from the University of Georgia. Background in nucleoside synthesis for antiviral purposes. Extensive knowledge in the drug development pipeline, including API synthesis, toxicology in-vitro testing, formulation development, FDA regulations (cGMP/21 CFR 210/211), pharmaceutical analysis, and more.

Graduate work focused on medicinal chemistry, specifically on antiviral nucleoside analogs. Included leading projects, complex synthetic organic chemistry, analytical development (NMR, HPLC, LC, Mass Spec), and more.

Experienced in solid dosage formulation development, including acetaminophen tablets and piroxicam capsules. Hands-on experience with rotary tablet press, dissolution, TGA/DSC, disintegration, HPLC, spray dryer, and more.